In a remote village in Phetchabun, a northern Thai province, where most residents are of the Hmong ethnic minority, life is hard and occasionally dark.

The 17,000-strong village, called Khek Noi, is impoverished, and the villagers are poorly educated.

As the transit point in the drug trade between the Golden Triangle and Bangkok, the village has different drugs circulating among the population, including among its youth. Glue-sniffing is rampant, snaring children as young as six.

Domestic abuse cases are common: there are cases of battered wives and children sexually assaulted by their fathers. Some mothers have also sold their children into prostitution, or to organ harvesters.

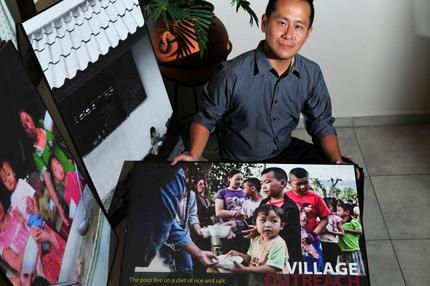

Amid these sad stories, a small relief agency, operating out of a concrete building located next to a graveyard, has been making a difference. Called Radion International, the Christian non-profit group was set up by Singaporean Eugene Wee eight years ago.

It is a Singapore-registered non-government organisation (NGO) and most of its donors are Singaporean.

The agency runs a farm, microenterprises and anti-drug programmes, shelters battered women and has rehabilitation shelters for high-risk children.

One of its most transformative initiatives is the Streetkids Program, where a sponsor covers a child’s school fees, uniform costs, transportation, medical care, allowance and shelter.

The programme has since expanded to cover secondary school education in Chiang Mai, as educational opportunities for the children are limited after they complete primary school in the village. More than 100 kids have benefited from this.

Radion’s story is remarkable on several counts, not least due to the hope and change an aid agency can offer to underprivileged communities. But Radion’s story is also a story about one man’s determination to improve the lives of others.

How it all began

It all began after Mr Wee, 34, came to know about a refugee camp with Hmong refugees from Laos.

The Hmong are an ethnic group from the mountainous regions of China, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. The Laotian Hmong have faced government persecution for generations, not least because they backed American forces during the Vietnam War. After the communists won the war, the new government swore to wipe them out. Thousands of them were forced to seek asylum in Thailand.

“There were about 8,400 people in this camp. They had insufficient fresh food, were depressed, and suicide rates were high. I felt compelled to help,” says Mr Wee, adding that there were no big-name humanitarian agencies helping out there except Doctors Without Borders.

He decided to dedicate a year volunteering there. He quit his defence-related job, cancelled buying his sports car and sold his stock portfolio, which amounted to more than $50,000.

“My mother thought I was mad. Thinking back, I was mad,” he says.

Needing a “base camp” of sorts while waiting for access permits to enter the refugee camp, he set up Radion International in 2007 in a shophouse together with a Singaporean friend in Khek Noi village, which was en route to the camp.

Radion started out serving the needs of the Hmong Lao in the refugee camp, but later focused its energies on Khek Noi’s Hmong Thai.

With four computer terminals, Radion’s first office was also the village’s first Internet cafe.

Before long, the cafe attracted the village’s five most notorious gangsters, aged between 12 and 15.

They came initially for the Internet, but soon asked Mr Wee to house them as their families did not want them.

He agreed, but on condition that they did not come home high on drugs. The five boys agreed and were drug-free six months after Mr Wee’s continuous efforts to counsel and help them.

Villagers also began to inform him of domestic violence cases.

One of the most horrific cases of child abuse involved three siblings kept in the jungle by their stepfather to look after his livestock and keep house, and who hit and shot at them when he was angry.

“When we went to rescue them, they were like wild animals running around in fear, without social skills and with the ability to communicate only in grunts,” Mr Wee says.

He wanted to do more, but money was running out. Radion had been spending most of its money on food and necessities for the Hmong Lao refugees in the camp – the agency’s original target group.

In 2008, he started a blog to get the word out about the plight of the children in the village. Enough Singaporeans responded for there to be a 1:1 ratio of donors to children – that was how the first Streetkids Program began.

In 2009, Mr Wee had enough funds to start a farm to provide employment for impoverished households. The money came from private donors, as well as from profits from Radion Enterprise, a social enterprise which he started in 2007 providing consultancy services and training for start-ups and NGOs.

By then, he was running community development programmes, teaching families everything from personal hygiene to food preparation techniques.

That year, his parents made their first trip up to Phetchabun. Mr Wee has an older sister, 38, who works in risk management. His mother, Mrs Christie Wee, 65, says she had been “very unhappy” with her son’s “drastic move” in 2007.

Seeing her son’s lifestyle there pained her even more.

“I didn’t understand why he gave up his King Koil bed to sleep on the floor. I saw him bathing with muddy water infested with mosquito larvae, and sometimes eating plain rice and vegetables. Even the children he was taking care of were getting better food and bedding than he was,” she says.

“As a mother, you wonder, why is my son coming here to suffer like this?”

Parents’ blessing

Maternal anguish aside, she recognised that the work her son was doing was meaningful and told him he had their blessing. Mr Wee’s father, Mr Charlie Wee, 70, is a semi- retired remisier.

Mr Wee shrugs off his mother’s comments. “In the past few years, I’ve never been poorer, but I’ve also never been happier,” he says. “These people are fighting to survive. They need people to believe in them and love them. If we continue to give them hope, we can change the course of destiny for some of them.” This conviction has kept him going all these years.

Radion’s assistance to the Hmong Lao refugees ended in 2010 because they were repatriated to Laos. Mr Wee’s partner decided to return to Singapore in 2010, but the organisation’s efforts with the village have continued.

Corporate communications executive Nicole Yeong, 38, who has been a donor with Radion for the past three years and who volunteered with the organisation earlier this year, says she was struck by the warmth of the children at the shelter.

“They have been so hurt and betrayed by adults, but yet they are open to strangers like me. Their willingness to sit near me and reach out for my hand shows me that they feel safe and happy in the shelter,” she says.

Radion also shelters needy or abused wives and visits the abandoned elderly to ensure their needs are taken care of.

Fifteen staff, most of whom are local Hmong, work with Mr Wee in various roles, covering everything from donor relations to accounts to being the children’s caregivers.

He says the organisation can run comfortably with $40,000 to $50,000 a month, but usually receives between $20,000 and $30,000. This covers operations and salaries. Mr Wee draws a “very minimal salary”. Radion is raising funds to construct an education and training centre to equip the villagers with skills to set up their own businesses.

Dr Boon Jiabin, 31, joined Radion as a director last year, after volunteering on several occasions with the organisation.

“Eugene has poured a lot of commitment, heart and passion into the work here over the past eight years and I can see tangible efforts. I believe in what Radion does,” says the general practitioner, adding that he is impressed by how Mr Wee has gained the villagers’ trust with his ability to speak fluent Thai and by working closely with the village heads and local police.

Mr Wee says when he can no longer continue the work, he hopes the villagers can take over.

“For now, I will not give up on these people. Lives are being transformed – that keeps me going,” he says.

Source: The Straits Times